Age:

High School

Reading Level: 3.7

Chapter One: I Feel Good!

I nodded to Kenji from across the stage. He was wailing away on his bass, but he nodded back. Our drummer Yusuf’s thundering backbeat was winding up to a climax. X, our lead singer, was screeching out a banshee wail.

Kenji and I jumped up onto the drummer riser, which was about three feet off the stage. We leapt off it in unison, our guitars held high over our heads. At the same moment, the stage lights started strobing in six different colors.

As Kenji and I flew through the air, Yusuf executed a perfect triplet roll. He built up to a long rattle with his splash cymbals. X dropped to his knees. He turned his face up to the rafters, squeezed his eyes shut, and held the microphone near his mouth. He held that same banshee note. My bassist and I landed on either side of X.

I gunned a final power E chord on my Fender Strat. You could barely hear it because the crowd in the Royal Oak Music Theater was going insane. I mean C-R-A-Z-Y. Every single person in the place was on their feet and screaming. My heart pounded like I’d just run a marathon. I thought that I’d lost a gallon of water in sweat over the course of our hour-long set.

X leapt to his feet, impressively unfolding his lanky, six-foot frame in the blink of an eye. His huge, basketball-sized Afro floated around his head. He was grinning from ear to ear. So was Kenji. We stared at each other. I realized I was grinning, too. I was grinning so hard my face hurt.

I spun around and looked at Yusuf. He was standing behind his kit, sticks raised high in the air. On his head was his trademark straw cowboy hat. It had an American flag bandanna wrapped around the crown and a ragged hole in the side. That hole was the result of an encounter with a nasty neighborhood knucklehead a couple of years back. It was right after Yusuf and his family moved to America from Syria.

The crowd was going berserk. The yelling soon turned into a chant: “MORE! MORE! MORE! MORE!” The sound filled the old music hall like an explosion of audio confetti.

Yusuf bounded out from around his kit. He joined the rest of us at the front of the stage. We all lined up and draped our arms over each other’s shoulders. We took a deep, dramatic bow. Yusuf whipped his hat off just in time to avoid losing it into the crowd.

“MORE! MORE! MORE! MORE!” The chant kept going, and we bowed again. Then we all looked at each other. There was no need to say anything (not that we would have been able to hear each other, anyway). Each of us knew what the others were thinking.

As if on cue, the crowd’s chant morphed into, “I FEEL GOOD! I FEEL GOOD! I FEEL GOOD!”

“Yeah, baby, we know what you want!” X shouted into his mic. “That’s right! We hear you! The People Movers hear you!”

The chant dissolved into wild screaming again.

We got back into place. Yusuf ran behind his kit. He rolled off a couple of quick licks and a cymbal crash. Kenji and I retreated to opposite sides of the stage. X stayed at the front. When he saw we were ready, he counted off, “ONE! TWO! ONETWOTHREEFOUR!!”

We swung into our signature tune. It was a cover of James Brown’s “I Feel Good.” X did the Godfather of Soul justice not only with his singing but with his moves. We were giving the people what they wanted. We were all right in time, and let me tell you, it felt freaking amazing.

But the best and craziest part came towards the end of the song. We’d decided to do a little experimenting with pyrotechnics. We used a flashpot X had bought from a theatrical supply company. The little device was planted behind Yusuf’s drum riser. Yusuf had a remote-control pedal that he would press at a certain point in the song.

And the thing worked. In fact, that’s an understatement. Flames shot up behind Yusuf. Smoke billowed up so thick that it enveloped Yusuf, his drums, and a moment later, the rest of the stage.

The crowd loved it. Us, not so much. It took twenty minutes for us to stop coughing. Our eyes watered for an hour afterward. And the people who ran St. Andrews… Let’s just say we were invited to leave and not come back for a very long time.

We made the local paper the next day. The front-page headline said, “Local Band is Smokin’ Hot!”

Chapter Two: Fun With Magnesium

You’re probably wondering who I am. I’m Carlos Villareal. I’m seventeen, and I’m in a band called the People Movers. I play lead guitar, Kenji Omura is on bass, Yusuf Karout is on drums, and Xavier Maplethorpe is on lead vocals (everyone just calls him X).

We live in Rochester, Michigan. It’s a little way north of Detroit. We started out just playing around in my garage back when we were high school freshmen. Things have gotten more serious now. We actually make a little bit of money from our music. They say money ruins everything, but so far it is a lot better than delivering pizza or washing dishes.

Why the name People Movers? It started as kind of a joke, really. Back when we started the band, while we were brainstorming names, X made a crack about Detroit’s People Mover. It’s an elevated train that makes a pretty useless little circle around a few downtown attractions. X had said that the People Mover didn’t move any people. He said they should call it the Ghost Train instead. Then I said that our band made people move (at least we hoped it would), so maybe we should take the People Mover name.

Everyone had laughed… at first. But the more we brainstormed, the more it made sense. We just added the “s” since there were four of us. We play funk and rhythm-and-blues. Music that makes people get up and move. You feel me?

* * *

The next day, we were all still riding on the adrenaline from the Royal Oak show. We were hanging out in my garage on Alice Street in Rochester. The garage door was open. Bright summer sunlight streamed in, along with muggy heat. Normally, we’d be jamming, since my garage was our practice space. But today, X was showing us the wonders of magnesium.

When I say magnesium, I don’t mean the stuff you get in nutrition pills. Well, it is the same, but the stuff we had was pure. In the pills, magnesium is combined with other stuff so you can’t see it for what it really is.

We all stood around a small workbench against one wall of the garage. X had a thick, steel canister with a small pile of dull gray metal shavings in it. He placed the canister on the bench. He held one of those long lighters you use for fireplaces and barbeques, the kind with a little trigger on it.

“You sure this is safe?” I asked, thinking of all our band gear piled around us.

“No worries, C-man,” X said. “The thickness of the can is exactly ten percent more than it needs to be to absorb the heat output of ten grams of burning magnesium.”

“You figured that out, huh?”

“'Course I did. I don’t wanna burn your house down. Now let’s get on with the demo. I think this stuff will make a righteous stage effect if we learn how to use it right.”

Kenji, Yusuf, and I all took a step back from the bench. X flicked the flame on and touched it to the metal shavings.

The reaction was instantaneous. A brilliant miniature fireball of pure white heat flared inside the can, lighting up everything within five feet of it. Wisps of smoke poured from the can, and the whole thing made a loud hissing sound. I could feel warmth from the can even from several steps away.

As we watched, the steel walls of the can began to turn a dull red.

“Uh, dude,” I said. “That can’s going to melt.”

“No, it ain’t,” said X, smiling.

The can turned bright crimson. The hissing, white-hot fireball continued to blaze inside it.

“You have a fire extinguisher, right?” Yusuf asked me.

I nodded, jerking my thumb at the fat, red cylinder hanging just inside the garage door. I kept my eyes on the can, waiting for it to vaporize and release a raging chemical inferno. But that didn’t happen. Just as the metal of the can was beginning to warp, the light died down and sputtered out. The can’s glow faded. The heat dissipated.

X grabbed a pair of barbecue tongs from the wall of the garage and picked up the can. He showed it to us. It was blackened and bent but intact. The magnesium itself was gone except for a thin layer of black ash on the bottom of the can.

“See? Cool, right?”

“Where’d you get this stuff?” Kenji asked.

“Amazon.”

I started to laugh, then realized he was serious.

“Magnesium is awesome,” Yusuf said. “We should use it in our next show.”

“Skins man has spoken!” said X, fist bumping our drummer.

Yusuf’s cell phone rang.

“Hi, ummu,” he said, using the Arabic word for mom. “What’s going on?”

Whatever she said next made Yusuf frown. She spoke for about thirty seconds. Then Yusuf said, “Okay, I’ll be there in a few minutes.” Then he ended the call.

“What was that about?” Kenji said.

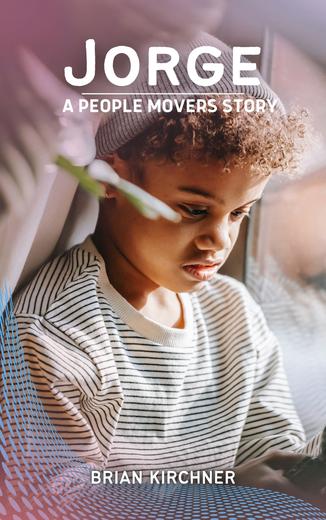

“Kind of hard to explain,” he replied. “There’s a kid at our apartment. He’s a refugee from El Salvador. He just got there.”

“Uh, dude, why is there a Central American kid at your apartment?” I asked.

Instead of giving a direct answer, Yusuf just said, “Because it’s Allah’s will. Come on. Let’s go over there.”

Chapter Three: Underground Railroad

If you’ve never been lucky enough to spend time in the home of a family from the Middle East, then it’s hard for me to describe the combination of smells that hit me as I entered Yusuf’s house. I had been in the Karouts' apartment many times, but the smells never failed to spin my head around. Today, I smelled a mix of spices, garlic, incense, and five or six other scents I couldn’t identify.

“Ummu!” called Yusuf, walking toward the kitchen. “Mom! Who’s that— oh, hi, abbun. Pop, where’s Mom? She said a kid showed up a while ago.”

Yusuf stood just inside the kitchen. We all gathered behind him. Yusuf’s father, a slight, balding man with wiry arms and intense, intelligent eyes, was preparing a small meal. He smiled when he saw us.

“As-salaam ‘alaykum, boys,” he said. He bowed slightly and placed his right hand over his heart. We all responded with “Wa-alaykum salaam, Mr. Karout,” and returned the gesture. Yusuf had taught us the traditional Muslim greeting shortly after joining our band.

Mr. Karout’s smile faded. “Yes, Yusuf. There is a child here, a refugee from El Salvador. He is with your mother in your bedroom. He doesn’t speak any English, only Spanish. He is very frightened. Sayeed brought him from Toledo. Very young, perhaps only seven years old.”

Mr. Karout shook his head sadly. “This separation of families policy… na uzo billah! Allah protect us!”

“Maybe you should tell my friends about what we’ve been doing,” said Yusuf.

Mr. Karout nodded. “We assist refugees who are trying to get into Canada. Others like us, such as our good friend Sayeed El-Saghir in Toledo, bring them to us. Then we help them with the final step in their journey. Being so close to the Canadian border here makes us an ideal last stop.”

“You mean, you guys have been running, like, an underground railroad for refugee kids?” I said.

Mr. Karout looked me with a puzzled expression. “Underground—?”

“Slaves, abbun,” explained Yusuf. “In the nineteenth century in America, when people would help slaves escape to freedom, they called it the Underground Railroad.”

Mr. Karout nodded thoughtfully. “Yes, something like that.”

“Totally cool,” said X. “You guys are legit heroes, Mr. K.”

Yusuf’s father continued. “No, we are just ordinary people. The Prophet Mohammad, peace be upon him, teaches us in the Holy Quran that it is the duty of every Muslim to extend hospitality to all guests, friends and strangers alike.

“This is especially true of those who are in extreme need, like we were when we first came to America. The three of you,” he said, looking at Kenji, X, and me in turn, “extended such hospitality to us. This is something for which I give great thanks to Allah every day.”

“Aw, Mr. K. We were just tryin’ to do the right thing,” said X.

Mr. Karout nodded. “Yes. It seems very straightforward, doesn’t it? But how much of the trouble in the world is caused by those who choose not to do the right thing? You helped us, even though you didn’t know us. Even though it might have resulted in trouble for yourselves from that bully.”

Mr. Karout was talking about the summer we met Yusuf and his family. A local fool by the name of Derek Bodley had decided he didn’t like having a Syrian family in the neighborhood. He had tried to frame Yusuf for some ugly graffiti spray-painted on the Bodley garage door.

Kenji, X, and I had proven that Bodley was the one behind it. Because of the Make America Safe Again Act (perpetrated by the same idiots in Washington who were responsible for the current crisis of refugee kids being separated from their parents) the Karouts would have been deported if Yusuf had taken the blame for the graffiti. One strike and you’re out, baby. Disgusting.

Bodley had also been the one who tore the hole in Yusuf’s straw hat. I asked Yusuf why he never fixed the hole or got rid of the hat. His answer had been short and right on: “Because I always want to remember how close my family came to losing everything.” My man Yusuf is a top-notch drummer and the bravest dude I know.

“Because of this enjoinment from the Prophet, and because we were refugees once, we are helping the children torn from their parents in any way we can. We take them in, we feed them, we hide them if necessary. And most of all, we show them kindness,” Mr. Karout explained. “This is what they need most of all.”