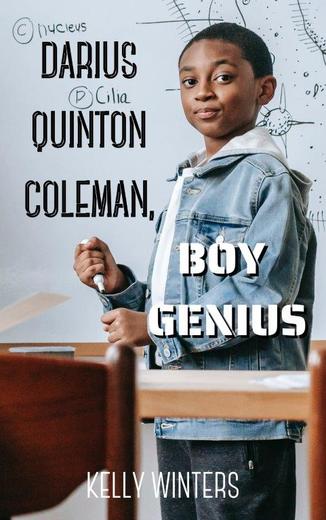

Age:

Late Elementary

Reading Level: 2.9

Chapter One

My mom figured out she had a problem on her hands when I was three.

She was taking a nap on the couch. I was supposed to be taking a nap in my room.

I found a screwdriver in the hall closet upstairs and took apart the safety gate at the top of our stairs. Then I went downstairs and dragged a stool across the kitchen floor, climbed up on it, and ate all the cookies she had hidden in the cupboard.

When I was four, I took apart the TV. When I was five, I put it back together.

When I was six, I was already making money by fixing fans, radios, and clocks for adults.

What I can't do, at least not very well, is read. I can look at a machine and then go home and draw every part of it from memory. But don't ask me to read the instruction book about how to use it, because I won't remember a word of it. I'll figure that out by doing it.

My parents say I'm just like my great-grandfather, Darius Quinton, the first Black aviator on Long Island. Back in 1916, he built his own airplane and flew it. He also invented all kinds of crazy machines. He left behind a lab filled with his drawings, his machines, and his airplane.

I inherited all of it. I also inherited his name. I'm Darius Quinton Coleman. Some people call me the Boy Genius.

My mother also inherited his mechanical ability, and she's the one who passed it on to me. She's an artist who paints portraits for a living, but she can make or fix pretty much anything. She made a spinning wheel out of an old bicycle wheel, spun up a lot of yarn, and knitted me a sweater. She built a greenhouse in our yard using old windows other people threw away. She built a beehive out of boards from a shed the neighbors tore down, and caught a swarm of wild bees to live in it. Every morning we have honey from that hive on toast.

My dad is a math professor at the New York Institute of Technology. He is not mechanically minded. He can change a light bulb, that's about it, but he's not exactly stupid, either.

We all live in my great-grandfather's house, a big, old, rambling place overlooking Clammer's Bay and Long Island Sound. He built it back in 1920 with money he made from his inventions.

When I was little, my great-grandfather was an old, old man, but still as smart as ever. He taught me his version of the principles of physics: "A body in motion stays in motion until friction stops it. A body at rest stays at rest. So, Darius, never rest. Keep moving, and keep learning."

He died when I was ten, and he was 110 years old. His gravestone says, "Friction Finally Got Me."

I still miss him. But I try to follow his advice, and I'm going to be an inventor like him.

Chapter Two

One Saturday, I was sitting in my lab. I was drawing a machine that I wanted to invent. It was a wasp-killing machine. My mother would be happy, because the wasps were always trying to get into her beehive and kill the bees.

Someone knocked on the door. I looked out the window. It was a kid. At first, it looked like a boy. But when I opened the door, I saw that it was a girl. A girl who lived two houses down from mine.

"Hi, I'm Annie," she said. She was wearing running shoes, jeans, and a shirt that said Green Bay Packers. She had muscles in her arms like a boy, and a boy's way of walking. Her hair was braided into tight cornrows.

"Hi, I'm Darius," I said.

"I heard you're a genius," she said.

"Some people say that," I said. I don't like to brag.

"Listen, if you're so smart, maybe you can help me with something. I have a mystery."

I love a good mystery. I had never had the chance to solve one before, but I had always wanted to.

"OK, what's your mystery?" I asked.

"You know the empty house in between your house and my house? Some new people moved into it a couple of weeks ago. And they're odd. Not odd in a fun, interesting way, but odd in a way that might be criminal. In fact, I think they're crooks."

"What do you think they're doing?"

"That's the problem. I don't know. But they're very secretive. They don't talk to anyone. They always have all their shades down."

"They could just be shy."

"I don't think so. I saw them, and they look pretty tough. Not shy."

"Are they those three white guys who drive that black Cadillac?"

"That's them."

"I've seen them when I'm out on my bike."

One blond, one brown-haired, and one with red hair. Otherwise they all looked alike. Tough. And mean.

"What do you think they're doing?" I asked.

"I have no idea. I just think they're up to something."

"Why don't you call the cops? Or tell your parents?"

"You know how adults are. They never believe anything a kid tells them. They'd say I was being overdramatic."

She was right. I had heard adults say that before. My parents usually didn't. They would probably be interested if I told them about these shady new neighbors. But I like to solve my own problems. It's more of a challenge that way.

"Sounds like you have a case," I said. I put out my hand for her to shake. "Delighted to work with you, Annie. Come on in."

Chapter Three

I love to see the look on people's faces when they see my lab. It's an old barn with huge skylights in the roof. Filled with sunshine, but also filled with machines. All kinds of machines, from many years ago. Big brass gears, levers, pulleys, drive belts, drive chains, telescopes, distillers, generators, test tubes, dials, steam engines. And at the back of the barn, hanging from the rafters under the biggest skylight of all, my great-grandfather's hand-built airplane, the Spirit of Freedom.

When you open the door of the lab, it trips a lever. The lever makes brass gears spin. The gears set drive belts in motion. They start steel balls rolling. The balls hit other balls, which ride along tracks set into the walls. A rolling chain of motion, things falling, bells ringing, lights turning on, motors lifting up more steel balls, which spiral down curling tracks past musical metal prongs, bouncing into tunnels, hitting switches, turning on all the lights and the radio. It's amazing to watch and listen to, and it always makes me laugh. Just from opening the door, you get all kinds of energy and sound and movement. It's like my great-grandfather is saying, Let your mind wake up. Let the thinking begin.

Annie stood in the doorway, watching all the steel balls rolling, gears turning, lights turning on. She lifted her eyes to the high ceiling, looking at the bright blue plane with its wide, white wings.

"Wow," was all she said.

She looked around at the tables full of tools, beakers, burners, test tubes, goggles, and heavy gloves. On the walls were old posters showing men and women in flying machines. Many of them featured my great-grandfather standing next to his plane.

"Where did you get all this stuff?" she asked.

"It was my great-grandfather's. He was an inventor."

"What did he invent?"

"He invented a very small, very necessary screw. Every motor on the planet has that screw in it. He only made one one-hundredth of a penny on each one he sold, but he sold a lot of them. Millions. Then he used the money he made to pay for his other inventions."

"What else did he invent?"

"He started out trying to make a flying machine. Have you ever seen those old movies of people trying to invent machines that would fly? Guys wearing goggles and riding contraptions with wings, trying to get off the ground? That was him."

"Cool."

"He didn't invent anything that could fly. But after the Wright brothers invented the airplane, he built one like theirs. He was the first Black aviator on Long Island, back in 1912. He used to go to the Hempstead Plains and fly his airplane — they called them 'aeroplanes' back then."

"Wow. What else did he do?"

"He invented all kinds of things that you will never see. Tiny parts. But they're all needed to make other machines work. See those old wooden filing cabinets over there? They're full of drawings of all the ideas he had. I think he was way ahead of his time. I think someday, people will look at his drawings and think, 'Oh, that's what he was doing! Let's make this thing!' and it will turn out to be just what humanity needs."

"This is amazing," she said. She looked around some more. "It's like a museum."

"Except it's more fun than a museum, because I get to use everything in it. Except the airplane. My parents won't let me fly it. Yet."

She sat down at my drawing table.

"OK," I said. "Tell me about these criminal neighbors."